On the borderline: The different synthesis styles of the world

You can tell the difference between an American synth, a British one and a Japanese one by sound alone. Find out how to in this guide.

Korg Opsix synthesizer. Image: Olly Curtis/Future Publishing via Getty Images

What do we mean when we say an analogue synth has an American or Japanese sound? In our recent review of Black Corporation’s ISE-NIN, we said that it’s “very Japanese-sounding.” This means its overall sound follows the general trend of Japanese synthesizers having a sound that’s clean and precise but powerful where it counts.

There are four main synthesizer-manufacturing countries: America, Japan, England and Germany. Just as each of these nations has its own cultural characteristics, so too do the sound of their synthesizers. You’ve probably played a Moog or heard one in a YouTube demo video and thought, “Wow, that’s beefy!” On the other hand, you may have noticed that Japanese synths tend to be more understated and subtle. This is largely due to the specific combination of oscillators and filters.

Of course, not every instrument from a nation will follow these rules but the trend is true enough that generalizations can be comfortably made.

Everything is big in America

Bob Moog developed the first commercial music synthesizer in 1964 with his modular creations. Although synthesizers existed before this in different forms, Moog did two things that set his apart. The first was the voltage-controlled oscillator. Pegging the pitch of the oscillator to a keyboard made the synthesizer playable in a musical way. He also pioneered the use of the filter as a tone-shaping component.

Oscillators and filters. When we talk about the sound of a synthesizer, this is fundamentally what we mean. Moog primed the pump with his early modular systems and laid the blueprint with the Minimoog Model D in 1970. Both feature massive-sounding oscillators; brawny and strong, they command the room, stage or mix. If you’ve ever put finger to keyboard on a Moog synth, you can understand why Gary Numan was so inspired by the sound that he abandoned guitars in favour of synths, or why Memorymoog owners sometimes complain that the polyphonic Moog is a little too powerful.

The Moog Ladder filter is also a commanding sonic presence. More than just a way to temper frequencies, its creamy contours – coupled with the musical resonant bump – excite and exaggerate the sound of the oscillators. It’s a potent combination that is very much still in demand today.

Moog was American, so it makes sense that his instrument would tend towards the big and powerful. To make a cultural metaphor, America can be seen to be advocating of freedom, with the needs of the one (or the One, to bring it back to Moog) taking precedence over the group. It’s okay if your synth doesn’t fit in the mix so well so long as it dominates on the stage.

Another American manufacturer known for powerful oscillators is Oberheim. From the first SEM (Synthesizer Expander Module) in 1974 through to 2022’s OB-X8, Oberheim synths are revered for sounding absolutely massive. Wild and woolly oscillators stack into unison monsters. Add a little detune and some stereo spread and you have the ultimate expression of the American synthesizer sound.

While Bob was inventing subtractive synthesis on the east coast of America in New York, Don Buchla was simultaneously developing the West Coast sound in California. Based around foldable sine wave oscillators and low pass gates instead of filters, Don’s creations were sonically rich and timbrally exciting in a way different to Moog’s. Aimed at experimental musicians rather than traditional ones, his version of the American sound is uniquely individualistic and anti-authoritarian.

Japanese gentlemen, stand up please

Japan is also a large manufacturer of synthesizers. The so-called Big Three companies of Roland, Yamaha and Korg have released countless instruments over the years but it’s safe to say that there’s a defining characteristic to them: precise yet musical, with a tendency to sit well in the mix. Japan is a group-based society that values harmony in social interactions. It’s not a stretch to say that its analogue synthesizers (and modern digitals inspired by them) follow this same ethos.

The ISE-NIN that we mentioned at the beginning is a modern recreation of the Roland Jupiter-8. Upon its release, and despite the high price tag, the Jupiter-8 became the standard poly for music studios for just these reasons: it was musically precise and always fit in the mix. This doesn’t mean that it was underpowered in any way, just that it had the magical ability to work well with other instruments in a song.

Other Japanese analogue instruments from the 1970s and 1980s, such as Yamaha’s CS-80 and Korg’s Polysix, have similar characteristics. Beautiful and finely tuned, they are the Toyotas and Hondas of the synthesizer world. Compare them to an American muscle car-style Moog or Oberheim, with a V-8 oscillator engine, and the comparison should be clear.

Of course, a society is made up of individuals and not everyone will fall neatly in line. Korg’s MS range is proof of that. With its brash, screamy filters and steel fist oscillators, 1978’s MS-20 is more punk than synth pop and an outlier in the Japanese synthesizer pantheon. It is telling, though, that Korg swapped out the filters to more a conventional circuit for the second revision. There’s a saying in Japan: “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down.” Of course, these days, when you talk about the MS-20 filter, you’re talking about the more famous first revision.

The synth never sets on the British Empire

Compared to America and Japan, England’s synthesizer output is much smaller. And yet the country should not be forgotten when it comes to characterful synths. Less easy to define than the States and Japan, the UK is a bit of a wild card, with two major players helping to define its independently developed sound.

The first, of course, is EMS. Electronic Music Studios was formed in 1969 and is famous for its string of experimental and sonically cranky instruments, including the VCS 3 and Synthi A. With its synths famously adopted by the legendary BBC Radiophonic Workshop and space rock pioneers such as Pink Floyd and Hawkwind, the name EMS is practically synonymous with voltage-controlled experimentation.

The other larger-than-life presence in British synthesis is the late Chris Huggett. Huggett’s unique sonic fingerprint came from his trademark one-two punch of digital VCO and analogue VCF. At a time when digital elements in synthesis were few and far between, Huggett pioneered the use of digital oscillators in his Wasp (released under the name Electronic Dream Plant, or EDP, in 1978) and OSCar (as Oxford Synthesizer Company, or OSC, in 1983). Huggett went on to work for a number of other companies, most notably Novation, some of whose instruments carry on Huggett’s legacy.

Germania: Wavetable oscillators and Eurorack experimentation

Germany is the last visit on our whistle-stop tour of synthesizer countries. Unlike the first three, Germany has pioneered styles of synthesis rather than characteristics. Its two biggest contributions are the wavetable oscillator and the Eurorack format. Both have proven immensely influential to modern synthesis so they should not be overlooked when examining how countries contribute to synthesis.

Wolfgang Palm of Palm Products GmbH– better known to the world as PPG – is a Teutonic titan in the world of synthesis. He is best known for inventing wavetable synthesis, whereby the oscillator in a subtractive system is capable of playing back not just a single sample but an array of them. By scanning through the arrangement of samples (the ‘table’ of the name), users can create evolving sounds and textures, ones not possible with traditional analogue oscillators.

First released in the late 1970s, his PPG Wave instruments proved hugely popular with artists like Tangerine Dream and Depeche Mode. They sounded different from the usual analogue, of course, but being sample-based they were also flexible and imbued with a uniquely powerful sound. Fast forward to the 21st century, and Palm’s invention has become a dominant force in modern synthesis. A large number of synthesizers, both hard and soft, feature wavetable synthesis as part of their design. Modern dance music production is unthinkable without instruments like Massive, Serum, and Vital, and they’re all wavetable synths.

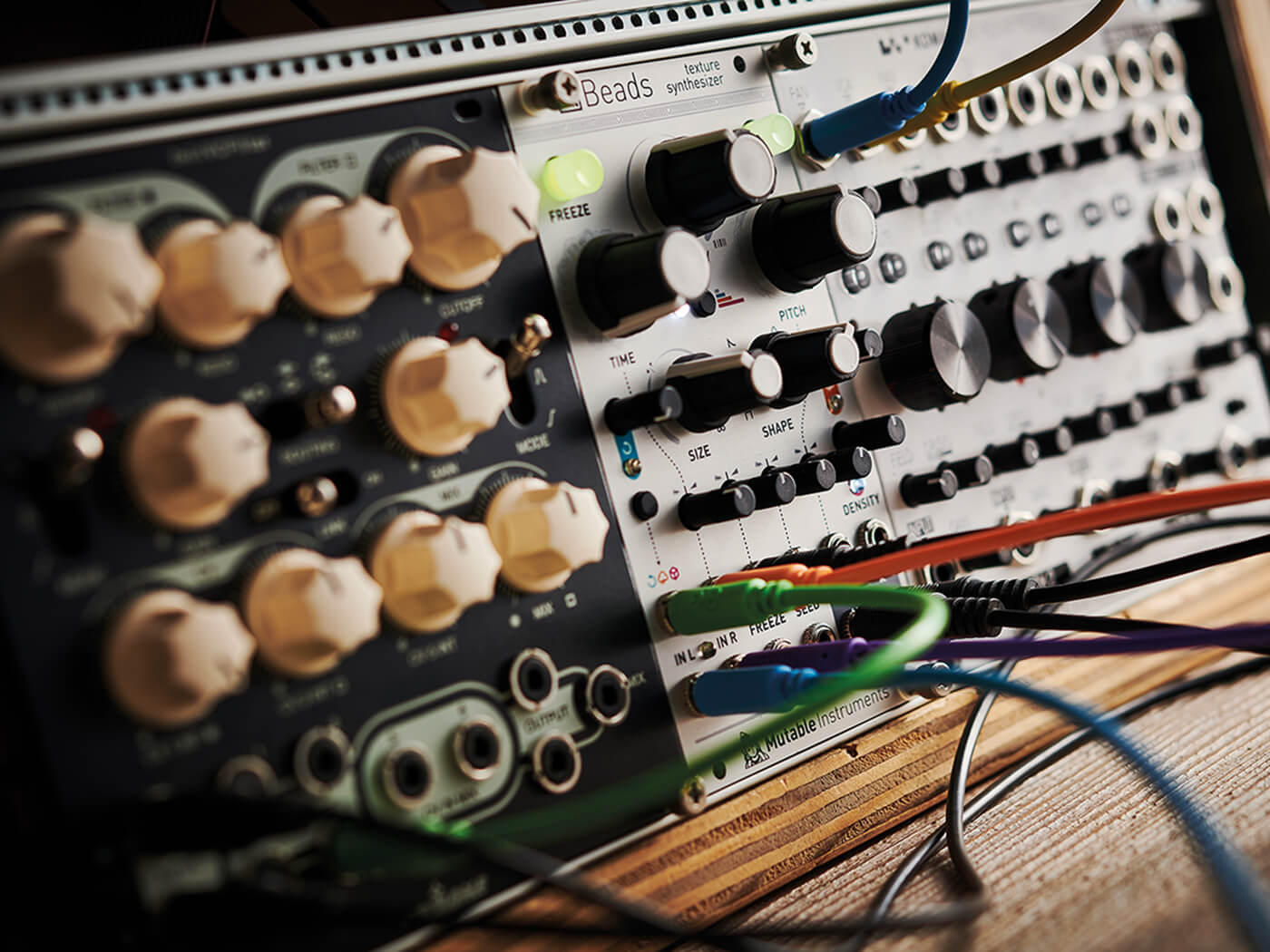

When looking at the state of modern synthesis, the other element that stands out is modular. Although one of the oldest methods of organizing synthesizers — that being in pieces that you assemble yourself into a cabinet rather than a prewired device — it’s exploded in the last 10 years or so. This is due entirely to the popularity of Eurorack, the brainchild of German company Doepfer.

In 1995, Doepfer released the A-100, a new modular system based around units that were three standard rack units high and two HP (Horizontal Pitch) wide. This was much smaller and more compact than traditional Moog or Buchla module sizes. And — crucially — they were more affordable. As time went on, more manufacturers began creating their own Eurorack-sized modules and cases. Now it’s become an industry unto itself, with everyone from small boutique outfits to established synthesizer companies like Moog and Behringer getting in on the Eurorack action.

What Doepfer’s creation has done is free synthesis from the shackles of normalled (prewired) synthesizer systems. With so many kinds of oscillators, filters, and other components available, you’re free to create any kind of instrument that you want. Dieter Doepfer didn’t set out to revolutionize the synthesizer world, however. This was no Prewired Reformation nailed to the doors of NAMM, just a man quietly making the kinds of instruments that he wanted. However, his invention helped liberate synthesis and introduce it to a whole new group of people attracted by the freedom and possibility of Eurorack.

The big blend

Many of the country characteristics explored here were set down in the early days of synthesizers. In our modern, interconnected times, it’s become common to mix and match components and thus national synthesizer styles. For example, the MiniFreak and MicroFreak, which come from a French company, Arturia, feature SEM filters borrowed from the American Oberheim. Some of Roland’s recent releases, such as the Jupiter-X, have multiple filter types, including Moog Ladder and Sequential Prophet-5 variants along with their own. This is even more common in software synthesizers, with varying filter types from the global history of synths all appearing under one drop-down menu roof. Eurorack has also helped encourage this trend, as mentioned, with individual modules of different oscillator and filter types available for mixing and matching.

As with fusion-style cooking, which borrows ingredients and spices from different cuisines and combines them into new dishes, modern synthesizers allow us to combine not only different synthesis styles such as analogue, FM and wavetable, but also the sonic characteristics of different countries. It’s an incredible time to be a musician and music producer, with the whole world available for our immediate use.