How Moog’s Minimoog Model D became a massive miniature icon

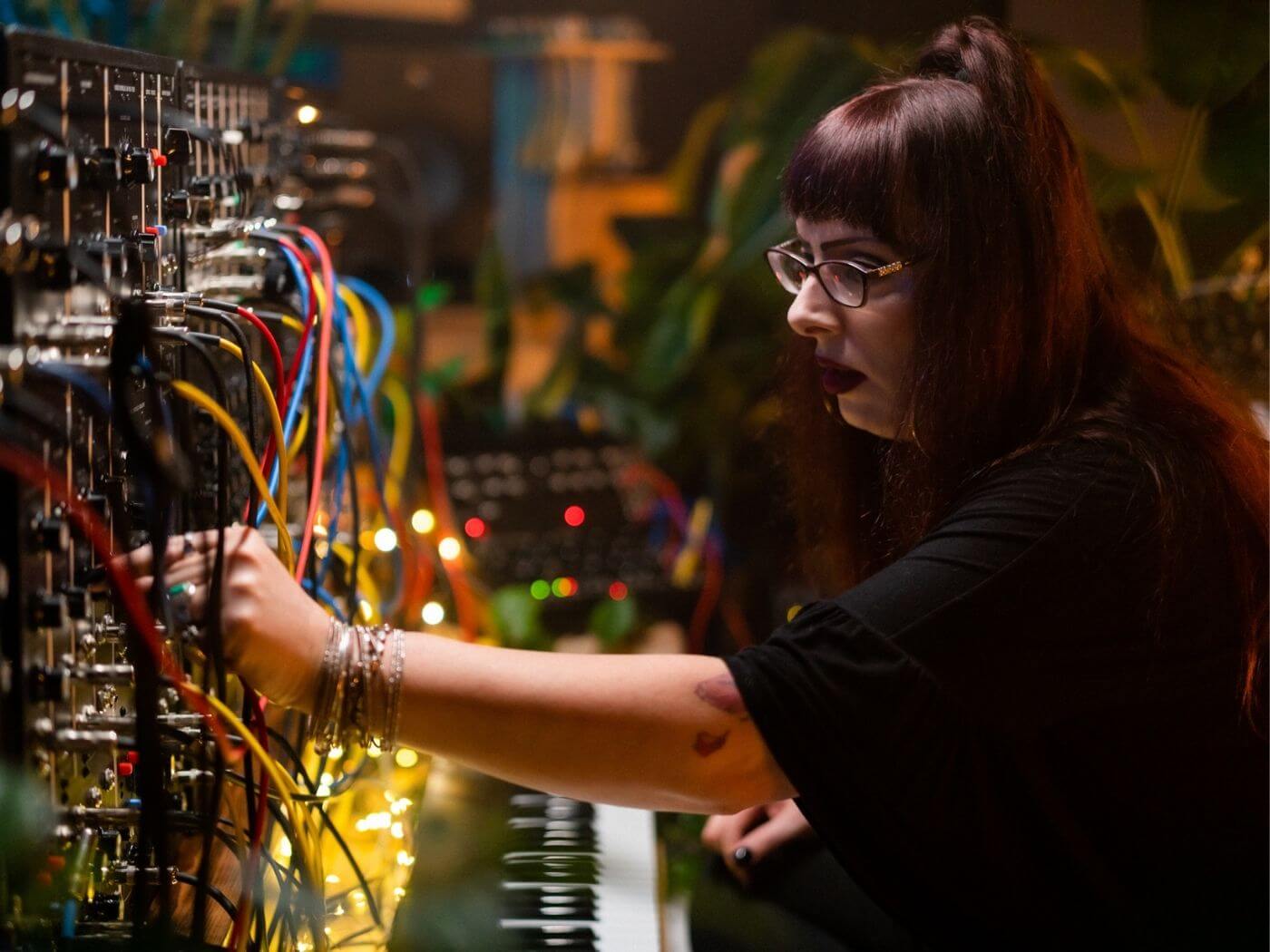

Lisa Bella Donna, Gareth Jones, Ashibah and Goldfrapp’s Will Gregory help us paint a portrait of one of the most revered instruments of all time.

Image: MusicTech

Log onto Moog’s website and you’ll enter a veritable theme park of synthesizer stimulation. Yes, you’ll find its compendium of successful, beautiful instruments, from the widely-acclaimed semi-modular Mother-32, DFAM and Subharmonicon to its Sub 25 and 37 models, as well as the formidable Moog One. But you’ll also find software, books, T-shirts, hats, water bottles, artwork, mugs and branded carry cups. There are films, education initiatives, events and competitions; all the calling cards of a company riding the wave of an iconic legacy. Wide-ranging and valuable these offerings may be but, of all Moog’s designs, by far its most celebrated and famous contribution to the world of music is the Minimoog Model D.

The Minimoog is in many ways the original synth. Of course, there were plenty of designs that preceded it, not least from Moog itself, but so iconic is the Minimoog that for most it has become the very figuration of the term ‘synthesizer’. It has been emulated and cloned in software and hardware countless times. One of Google’s most successful and memorable Google Doodles was a playable image of the Minimoog in tribute to Robert Moog’s 78th birthday. It is, in no uncertain terms, an icon.

Beginnings

The original Moog Synthesizer was a furniture-sized modular instrument, whose development began after a chance meeting in 1963 between Robert Moog and the composer Herbert Deutsch at a New York State School Music Association conference in Rochester, upstate New York.

Deutsch invited Moog to attend an electronic music concert in February 1964 at the studio of venerable American sculptor Jason Seley. “Let me say again that your concert was stimulating as well as enjoyable,” Moog wrote to Deutsch soon afterwards. “Give my regards to Steve and Jason. You might tell Jason that the RA Moog Co would consider one of his works to be an acceptable acquisition (Chutzpah? Whew!).”

“The first meeting lasted at least three hours in Rochester,” Deutsch told Roger Luther of Moog Archives in 2003. “After my February concert, Bob and I – with wives – went out to eat and talked about the possibility of a ‘small and affordable music synthesizer’.”

The quintessential success story of the Moog Synthesizer would come not from the world of pop music but from Baroque music. The eventual Minimoog’s classic walnut casing was more or less a product of Robert’s instrument-building ethos and his background in classical music. Wendy Carlos’ 1968 record Switched On Bach boldly tackled the composer’s titanic legacy head-on, successfully demonstrating the synthesizer as a musical instrument capable of rich and dynamic compositions in its own right.

Goldfrapp’s Will Gregory originally formed his 10-piece Moog Ensemble in 2005 for a one-off performance of Carlos’s work. With it, he has since performed compositions old and new all over the UK and Europe.

“Switched On Bach was the perfect synergy between monophonic synthesizers and Bach the composer,” Gregory tells MusicTech. “[Carlos] coloured each strand of the melody with such an individual sound – you dive into the music and can see all the individual lines around you.

“What you’re listening to when you hear an oscillator is electrons shooting down a wire,” he continues. “That’s quite mystical. You could argue it’s more earthy, more fundamental in terms of the physics than anything else, even acoustic instruments. But also, it’s not man-made. What you’re hearing is something that is not fundamentally produced by someone blowing or plucking or scraping, you’re listening to something that is on an atomic level. And that’s exciting.”

In the wake of Switched On Bach, sales of modular systems peaked in 1969 before plummeting almost immediately after. Despite subsequent similar releases, the success of Carlos’s momentous work could not be replicated. With a surplus of parts to reckon with, RA Moog Co was in trouble. It was after Bill Hemsath found himself rooting around in the attic of Moog HQ, nicknamed the ‘synthesizer graveyard’ for its piles of broken hardware and retired components, that things would change.

It was Hemsath who first thought to try compacting a series of modules into a desktop format, complete with a sawn-off keyboard.

Upon seeing this miniature ‘Min A’ for the first time, Robert Moog was mildly interested at best. Unperturbed, Hemsath continued to develop his idea, enlisting engineers Jim Scott and Chad Hunt to develop a ‘Min B’. By early 1970 another version, the ‘Min C’, was in development. By this time the company was facing severe financial pressure. RA Moog Co needed to come up with a marketable solution fast. Taking matters into their own hands, Moog’s engineers conspired to turn their miniature oddity into an actual product and set about producing a fourth iteration of the Minimoog: the Model D. Despite initially baulking at the idea (and berating his team for going behind his back), Robert Moog came around. His company’s fortunes were about to change.

At 14 kilograms, the Minimoog Model D is anything but miniature by modern standards. But next to its modular predecessors in 1970, it felt positively pocket-sized. The evolution from A to D is palpable; the Model A essentially resembled a compact modular system stuck to a keyboard, the Model B then adopted an inclined, purpose-built front panel, and the Model C went on to settle on a layout that would come to characterise the subsequent Model D, including its signature hinged pop-up panel.

“The Model D is the distillation of a lot of processes,” says Will Gregory, “into a format that was accessible to more lowly musicians without the wall space or the budget for a modular synthesizer. My first experience of it was that it had this punch to it. There’s something about the speed of the attack that is huge. It’s also got these low and warm oscillators.

“It doesn’t sound like some of the other American synthesizers, the Arps or the Oberheims, or the Japanese, like Roland. What they don’t have that the Minimoog has is this low, animalistic punch. Then you’ve got your modulation wheel with a variety of waveforms you can modulate your basic sound with, including white noise. And when you use white noise as your modulation source you really are plugging into the Big Bang. It growls.”

Keyboard or no keyboard?

Back in the early 1960s, one of Deutsch’s most crucial contributions to Moog’s original synthesizer design would come to characterise the Minimoog and synthesizer design the world over.

“When Bob questioned me on whether the instrument should have a regular keyboard,” he said, “I told Bob, ‘a keyboard is a good idea. After all, having a piano did not stop Schoenberg from developing twelve-tone music and putting a keyboard on the synthesizer would certainly make it a more sale-able product!’”

The inclusion of a keyboard might seem unremarkable through the modern lens but, for Moog, it was by no means the obvious thing to do. Others, such as composer and co-founder of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, Vladimir Ussachevsky, suggested Moog omit the keyboard design. Besides, on the other side of the USA, Don Buchla had not felt the need to include one on 1963’s 100 Series Modular Electronic Music System.

Discovering a classic

Veteran producer and expert synthesist Gareth Jones remains one such dissenter of the Minimoog’s keyboard. “I was never much of a Minimoog fan,” he says. “The main thing that put me off was that it has a keyboard, and I’m all about sequencing. So that was an irrelevance to me.”

Jones has been on the frontier of synthesizer innovation for upwards of 40 years, working on records by John Foxx, Interpol, Wire, and Depeche Mode’s Berlin Trilogy. Beyond this, he makes music solo, as Electrogenetic, and collaboratively, with venerable New York producer Nick Hook as Spiritual Friendship and with Daniel Miller as Sunroof.

“There’s a type of musician that doesn’t want to dick around with patching cables,” he tells us matter-of-factly. “It’s a simple iteration of East Coast subtractive synthesis. You feed oscillators into a filter, you hone the filter to shave off harmonics you don’t want, and then you shave the overall dynamic with a VCA. It’s really simple but that’s why it’s so effective. There are many musicians far more capable at the keyboard than I am who loved it because they were able to make new sounds and perform them on a keyboard.”

Minimoog’s earliest adopters, Herbie Hancock, Keith Emerson and Rick Wakeman, were enraptured by Moog’s innovation. The cascading free jazz of Sun Ra’s My Brother The Wind is thought to be the first use of a Minimoog in the studio; a record built around frenzied dialogues between the ensemble’s acoustic instruments and Sun Ra’s wildly unpredictable Min B.

“I was kind of prejudiced against the instrument,” Jones continues. “But one day I overcame all that and said, ‘Wait a minute, the sound of this thing is incredible!’ I was the opposite to Gary Numan, who had an epiphany when he first discovered the Minimoog.”

Gary Numan’s introduction to the Minimoog is, if nothing else, demonstrative of its accessibility. Numan noticed a Model D in the corner of the studio while recording with his then-punk band Tubeway Army in the late 70s.

“I’d never seen one before,” he told The Quietus in 2016. “I didn’t know how to set the Minimoog up so I just pressed a key for whatever it was set on and it made that famous Moog sound, that famous low growl, and the room vibrated. It was the most powerful thing. It was like an earthquake and I just loved it. And before the band was even finished setting up the gear I was in there working on changing the songs we’d arrived with into pseudo-electronic songs.”

“I didn’t have that at all,” says Gareth Jones with a laugh. “It’s been the reverse. I’ve come to love it later in life. As I started to work with people who own these instruments, I started to realise what a great instrument it was; what incredible bottom end; what a lovely, creative workflow, being able to mix the oscillators and the noise. Everything about it – the sound of the oscillators and the sound of the filter.”

Danish-Egyptian producer and DJ Ashibah has taken her dynamic house sets around the world, filling dancefloors from Brazil to Russia. Her first experience of the Minimoog was akin to Numan’s.

“The first time I came across a Minimoog was when my old studio partner brought his to the studio and I got to play with it,” Ashibah remembers. “I pretty much spent the whole day just playing with it without even pressing record.

“We had to get to know each other,” she continues. “The sound and feel was amazing and so inspiring. I love that it’s not too complex to use, which is great when you come to the studio full of creativity and want to get started. The sound of this synth is so mighty and dynamic. It elevates every production.”

Renowned synthesist, composer and artist Lisa Bella Donna is one of the modern faces of Moog Music Inc. Responsible for a range of patchbooks for their semi-modular Ecosystem, and the exploratory multi-timbral patches on the company’s flagship Moog One, she has demonstrated the power of Moog synthesizers as an educator, performer and ambassador for the company.

“The first Moog synthesizer I ever experienced was a Minimoog Model D,” she says. “This was in the mid-1980s. I was working at a commercial jingle studio and they owned the Minimoog and ARP Odyssey but they never used them on sessions. One day after a session, the house engineers left early. So I wandered into the storage room to see what other instruments were lurking and then uncovered the Minimoog.

“The moment I began to dial it up and play it, everything changed. It sounded alive and right up front, warm and pure, wild and at times unruly, which fascinated me immediately. The touch response, the range, the flexibility and, of course, the sound. It’s truly where my lifelong journey with synthesis began.”

Transcending technology

Many electronic instruments are superseded in quality and functionality by their successors, but as time has gone on the scope of the Minimoog has seemed to expand, not contract.

Will Gregory has found himself using the synthesizer in ways Robert Moog could never have foreseen in 1970. For instance, using MIDI wind controllers in his Moog Ensemble.

“What you do get from these instruments is a repetitive attack,” he says, demonstrating for us with a low, double-tongued note on a clarinet-like controller, fed through the Minimoog to create a growling flurry of saw wave tones. “You can’t do that rapid tonguing with your finger on a keyboard,” he explains. “There is something beautiful about the flexibility of playing with one of these. It opens up the generation before synthesizers in a way that was never thought about at that time.”

Gareth Jones has similarly experienced the Minimoog’s aptitude in the modern studio. “I had a 1938 Telefunken mic that we refurbished,” he says. “It had a wonderful sound – way better than the engineers could have heard at the time because mic preamps and monitoring have come on so much. It’s like that with the Minimoog.

“There was always a Minimoog during the Depeche Mode sessions I did – it was part of the toolkit. It was a little wasted then because, in the 1980s, there wasn’t as much bass on records. In a way, I’ve enjoyed the Minimoog more in the context of modern monitoring, with its tuneful and extended bottom end. Just being able to hear that more and more. It’s like, ‘Wait a minute! There’s an octave at the bottom we haven’t been using.’”

Despite the surfeit of top-quality modern synthesizers released every year, it’s almost impossible to imagine the Minimoog in its original form ever becoming redundant. “The Minimoog is an instrument that, no matter what goes in and out of style, will always be an instrument of the highest calibre, musically expressive and useful,” says Lisa Bella Donna.

“Thirty-five years of playing one and it’s my voice, an extension of my musical heart and spirit,” she continues. “I connect with it in ways that I don’t connect with any other instrument. Every time I take flight and explore with the Minimoog, I rejoice. It fills my heart with music.”

The Minimoog is a rare example of a piece of technology immune to the terminator of technological development. “You can’t live on one synthesizer alone,” reflects Will Gregory. “But I tell you what: you can go a long way with a Model D.”

For more gear features, click here.