Rise of the Maschines: The history of the Native Instruments’ production system

With the recently announced sea change of Native Instruments’ Maschine workstation from a software and hardware hybrid to a completely standalone hub, it’s high time for us to chart the legacy and development of this modern classic of music technology, and see how this remarkable transformation reflects larger shifts in our attitude to music-making in the 21st century.

It’s one of the world’s most widely-used music technology workstations, and with the advent of the newly launched Maschine +, now a completely self-sufficient way of making music without the need for a computer. But when this great unifier of hardware and software first manifested back in 2009, it appeared slightly out of step with a production landscape still very much in thrall to the magic of computer-based workflows. But this inaugural product was taking its cues from foundations set decades previously.

Terms like ‘MPC workflow’, ‘old-school sampling’, ‘finger-drumming’ and ‘hardware workflow’ are now universal terminology, however, this hasn’t always been the case. Although sample-based drum machines had arrived on the scene by the early 1980s, it wasn’t until later in those iconic ten years that the world was introduced to the machine that set the benchmark for so many ‘workstation’ designs that followed – the Akai MPC60.

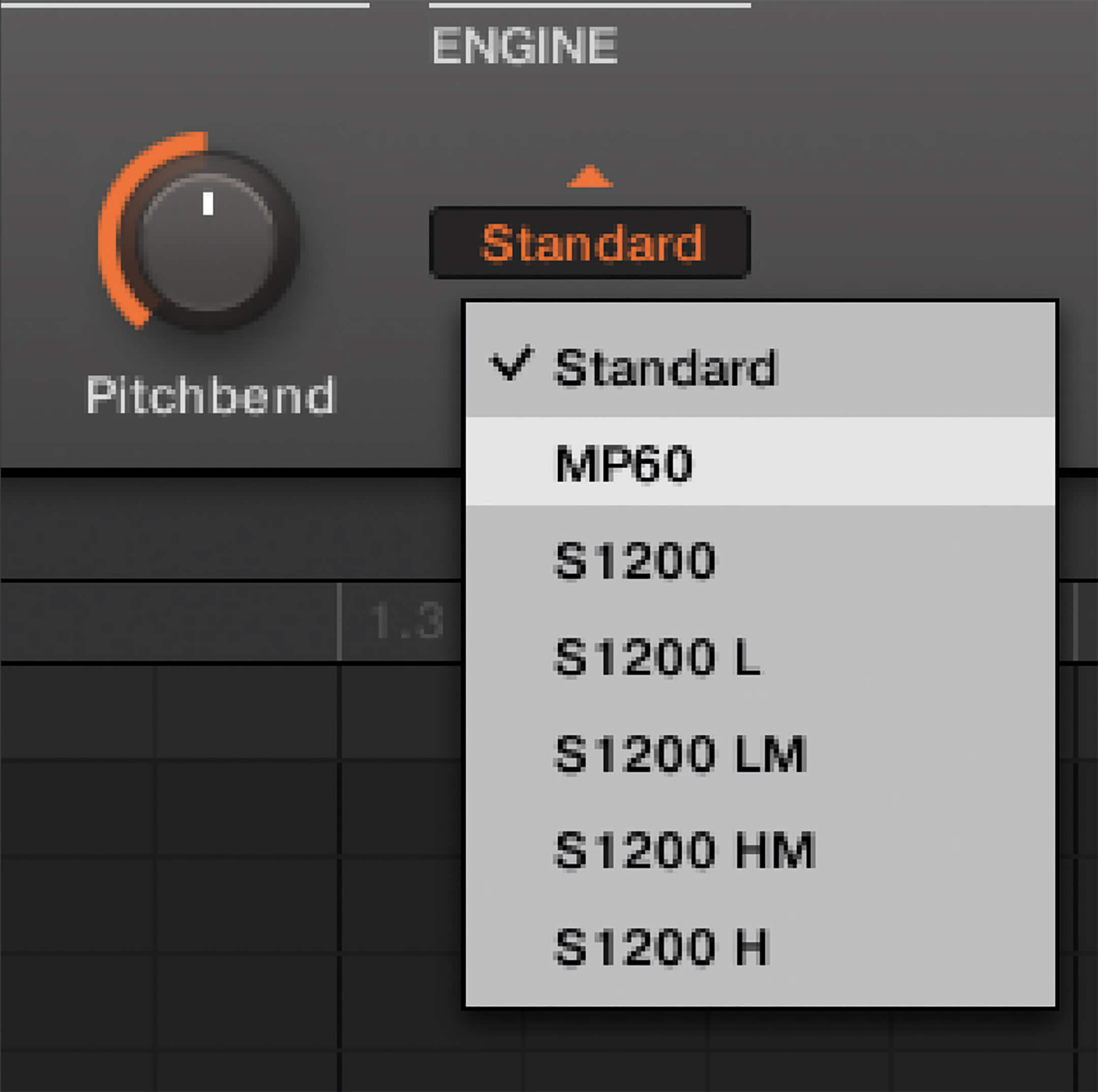

With navigation display screens across the top, 4 x 4 grid drum pads and various inputting buttons and a slider, it’s easy to see how the MPC layout became the forerunner for what’s still commonplace today with percussion-based MIDI controllers and workstations. Alongside the iconic physical, tactile workflow of earlier sampling machines came technical limitations. Historically, however, the 12-bit sampling restrictions of machines like the MPC60 and Emu’s SP-1200 machines, coupled with the character of their analogue to digital converters, allowed these machines to form part of a culture of sound that is still revered to this day.

Alongside Akai, other major companies created sampling machines with higher quality capabilities, larger memory capacities and higher polyphony. Some catered towards MIDI sequencing and sampling, others focussed purely on standalone sampling units with the user needing their own form of MIDI sequencer. These later hardware-based incarnations all have their own stories of success, but there was soon a major shift in music-making which happened towards the end of the 1990s that would alter the course the entire music production landscape forever.

Computer love

To set the scene for Maschine’s first arrival, it’s important to understand the major shifts through the 2000s. Towards the late 1990s, unless you were running a Commodore Amiga as your affordable 8-bit, domestic priced sequencer and sampler, the main accessible choice for bedroom producers was an Atari ST running Cubase for MIDI sequencing. This would require all sound sources to be external ie, hardware drum machines, sound modules, synthesisers and samplers. Around this time, a turning point occurred, as PCs (and pricey Macintoshes) were becoming powerful enough to run modest audio/MIDI sequencing and audio recording. VST plug-ins had already arrived in 1996, but coupled with VST Instruments (VSTi) in 1999, this represented a sea change in the standardised software-based studio and a move away from the costs of what were becoming perceived as dusty old hardware studio tools.

The start of this new era was when the accessibility of music-making started to broaden through virtualised studio environments. Alongside the evolution of more powerful and affordable home computers, the pain of a hardware recall soon became forgotten, replaced by the convenience of ‘saving all’. The role of the programmer also became more prominent with many new generations of creatives crafting their music using just a mouse and computer keyboard. For a while, if a musical inputting device was used, it was often a simple and affordable piano keyboard controller – far from the complexity of control and ease of workflow we’re used to today.

Rewriting the future

Over the years, as we collectively found comfort in our ‘all bells and whistles’ DAW environment, many developments took place between DAW design and MIDI controller software to create a more fluid, and musical, experience. Better bridging the gap between our in-the-box mechanics and a more tactile, hardware-oriented navigation and interaction. Highlights include Novation’s Automap system in 2005 which used adaptive mapping so as the user moved around the software, the Novation SL Controller would display relevant text and re-map its controls, making the user less reliant on the main computer display. Though Ableton Live had long been supporting Control Surface scripts for a variety of controllers, it was devices like Akai’s APC40 and Novation’s first Launchpad released in 2009 that helped move us further towards a hardware and software hybrid paradigm.

Native Instruments, which had been at the forefront of virtual instrument advancement through the noughties, decided that the time was nigh to offer a fully integrated hardware control experience, but with a software heart.

At this moment in time, Reason was at release version 4, Cubase at 5 and Digital Performer 6. Ableton Live, Pro Tools and Sonar were 8, and, FL Studio and Logic were 9. Though the Launchpad and the Akai APC 40 were released during this year, what set Maschine apart was the inclusion of its own sequencing software, making it feel more like the purchase of a ready-packaged music-making environment. Like the approach earlier versions of Propellerhead’s Reason took, Maschine virtualised a MIDI-based hardware studio offering a classic MIDI Sampler workflow, audio processing and virtual instruments. Much like a classic APC60 with the hardware you’d dream of buying, once you had won the lottery!

Though the software rapidly matured after its version 1.0 release, the Maschine MK1 hardware immediately offered the essential layout required by hip-hop makers of the time. That is, the classic 4×4 drum pads, portability, USB power and MIDI 5-pin I/O for external sequencing and sync. The software itself could be run as a plug-in within a more fully-featured DAW or it could run in standalone mode meaning it could easily fit into a variety of workflows.

Another key attribute of the inaugural Machine was that the initial process of playing and sequencing sounds was extremely straightforward and could be picked up after only a few minutes of interaction. Even if your background was in the traditional approach of linear sequencing from platforms like Cubase, Logic and Pro Tools, thinking in patterns didn’t take long to get used to.

The tactile flow and mindset of working with a hardware interface seemed to present the biggest attraction amongst the creative community. Whether it was for a studio environment or performing live, the earlier ‘hip-hop’ tag opened up as artists from various camps of music-making were seen using it. Artists subsequently seen with the Maschine platform over the years include Richie Hawtin (Plastikman), Run The Jewels, Jeremy Ellis, Icicle, Chemical Brothers, Eskmo, 9th Wonder and many more.

Evolution and minimalism

As the following decade gathered pace, the much more compact Maschine Mikro arrived in 2011. The Mikro allowed users to have the same main software system with a far more portable unit. The same 4×4 pads are included but a tab and sub-menu system allows navigation with a single dynamic data encoder. MIDI I/O is also excluded here so it was much more about wanting something that could slip in and out of a bag on the move, or wanting to invest less in the platform while still getting that unique feel of the MK 1 drum pads. The most striking evidence of the Mikro in use can be seen in ‘Battle Stance’ position by finger drumming virtuoso Jeremy Ellis (rotated on its side to put all pads nearer to the user and other controls out of the performers way). Sound-on-sound loop-based performer junk-E-cat also presents the more recent Mikro MK3 while flying on a paragliding trip using a custom rackmount kit.

The standard Maschine hardware and Mikro have both developed through three eras of evolution, the MK2 era saw an improved feel for the pads which changed from the orange theme of the MK1 to RGB colour schemes which helped navigation of sounds in the darkest of club and studio environments. The software also matured into version 1.8 at this point and finally added an offline time-stretch function to complete the old-school sampler feature-set, and offline pitch transposition for samples too. Transient master and saturation were also added to the effects processing suite, letting the user get more bite and presence out of beatmaking.

Battle of the beatmakers

The time shift from 2012 to 2013 was very important for those wanting their drum pad-based sequencer fix. Maschine’s MK2 models were released in late 2012 but Akai soon threw its hat into the ring with the Studio and Renaissance models. The former was a compact, USB-based controller to integrate with a bespoke MPC-like virtual environment. The Renaissance was the unit with an unmistakable ‘wow’-factor as it had a similar footprint and look to a classic MPC unit and offered various audio and MIDI I/O. Options were suddenly numerous for those looking for tactile beat-control, but Native soon answered back with their Rolls Royce ‘Studio’ model released later in 2013.

The Maschine Studio allowed the space for Native to lay out additional features. A plush-feeling jog dial could be used for various aspects of data entry and finer control. The standard pads sat in the lower middle but omitted any sign of Shift+ functionality, the Studio had space for dedicated buttons. When seeing this for the first time at the initial product demonstration, it wasn’t this expansive layout that kept our attention, it was the graphical, colour LCD screens. Until now we had been starved of colour and now users could experience the same detail of display as their computers could give. The unit offered more MIDI connectivity which helped further justify its ‘Studio’ monicker, but still relied on the user’s existing audio interface set-up.

Alongside this hardware advancement, the software reached 2.0 which, among many user-requested features being implemented, offered the excellent acoustically modelled drum synth instruments. These are a combination of easy to use and modify drum sounds that have a knack of constantly sitting in a sweet-spot wherever users tweaked them to, offering plenty of weight alongside a range of engaging timbres.

The Maschine Studio certainly filled the needs of those who sought a more refined music-making experience, though it did lack two things many still wanted: portability, and its own audio interface. Of course, the MK2 was there for easy bag packing but it wasn’t till the MK3 in 2017 that we saw the colour and details of the Studio’s LCD displays, onboard audio I/O and a major change in the drum pad design. This felt like a huge reward for those still using the MK2 standard hardware and could be powered on USB alone, removing the Studio’s need to be powered for those LCD’s to work.

Another feature to be handed down this time from the Maschine JAM (as detailed in the boxout) was a touch-sensitive Smart Strip to control MIDI- pitch, -modulation, the newer Performance FX and even achieve guitar-like note strumming by sliding across the strip. The Mikro received a similar specs update too but stayed true to its roots as a hardware controller only by only having USB I/O.

Standard MK3 features aside, the key change here was the ability to now turn up to perform at a show, or a friend’s studio with one piece of hardware and your computer. Or at home, have your mixer and turntables hooked up for vinyl sampling, and generally have a standard of connections to that talk in unison to your software.

Jam hot

Before we get to Native Instruments’ latest release, it’s worth looking at some of those other avenues of development that the Maschine went down. Jumping back to 2015 and 2016 respectively there are two other members of the Maschine family which offer a different take on the Maschine workflow. The first is iMaschine, a scaled-down version of the full software which is engineered to best serve an iPad or iPhone touchscreen user. There are various ways to input your music like the fully featured software, you can record directly into the app and it also lets you export your projects for finishing into the standard Maschine software.

The second is Maschine JAM. Though it’s now discontinued, it offered an interesting addition or replacement to the standard hardware workflow. Visually it had a clear Launchpad, APC and Push style layout with a much bigger grid of buttons. These could be used for playing melodies and drums but were not velocity-sensitive. The biggest strength of this unit was real-time pattern and scene cueing via the buttons, multi-lane step sequencing and the Smart Strips strips at the bottom were incredibly expressive for capturing detailed automation or to perform live. If you coupled the JAM with a standard Maschine controller it massively opened up the ways you could input your music and allowed for more forms of creative expression.

Plus size

That brings us to September’s launch of Maschine + which ushered in a new age for the Maschine legacy. This latest iteration combines all the features that gained respect from music makers over the years and packages this in a standalone form. Much more on this is explored in our in-depth review, but needless to say, as the demands of music makers have changed, so has the Maschine machine. As the trend of returning to standalone hardware has grown exponentially over the last decade, the ability to take a Maschine + unit down this ‘power-on and go’ route demonstrates Native’s answer to the growing competition and being astutely aware of the ever-shifting sands of the production world’s status quo.

With chief rival Akai also growing a standalone range of MPC style offerings, best represented by the Force device, this latest major move by Native Instruments very much cements the all-in-one approach. Technology has advanced to such a point that computer-oriented production approaches are no longer the default, and that equally as much sonic dexterity and music production ability is possible with just one device. Being able to use the best of both hardware and software worlds, while also engaging with the production process on a tactile level is the cornerstone of the Maschine ethos, and we’re keen to see where the unpredictable story will take us next.

Common set-up options

1. As a standalone hardware controller with the Maschine software (or just a Maschine+ alone)

2. Multiple plug-in instances of the Maschine software in a DAW being controlled one at a time by a Maschine controller (using the Instance button on the hardware)

3. Multiple plug-ins in one DAW and multiple different Maschine controllers for multiple users at one time (each controller set to a separate instance)

4. Multiple computers, a Maschine controller per computer and Ableton Link synchronisation over a shared network (perfect for studio or performance jams)

5. Maschine hardware set to MIDI mode and set-up to control other forms of software (many templates available for various DAWs, DJ software, etc)

For more features, click here.